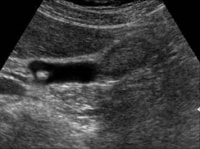

Gallbladder tumors are recognized with increasing frequency due to improvements in imaging techniques and increased utilization of these studies. Approximately 5% of patients evaluated with ultrasonography for abdominal pain will have a gallbladder polyp. Cancer of the gallbladder is uncommon, although it is the fifth most common gastrointestinal malignancy. The size of a gallbladder polyp is generally the strongest predictor of malignant transformation. (See image below.)

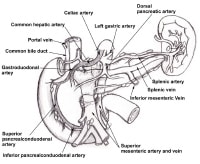

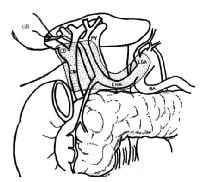

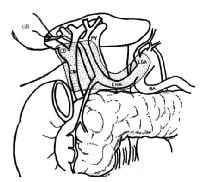

A schematic drawing of the extent of lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer, especially when the extrahepatic biliary tree is resected.

A schematic drawing of the extent of lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer, especially when the extrahepatic biliary tree is resected.

Benign lesions

Benign lesions of the gallbladder are relatively common, but only adenomatous polyps are considered to have malignant potential. Although ultrasonography can be useful in evaluating these lesions, considerable difficulty may be encountered in establishing the diagnosis preoperatively.

Cholesterol polyps

Cholesterol polyps account for approximately 50% of all polypoid lesions of the gallbladder.

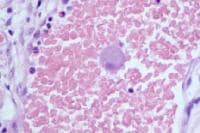

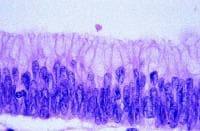

These lesions are thought to originate from a defect in cholesterol metabolism. They appear as yellow spots on the mucosal surface of the gallbladder and are identified histologically as epithelial-covered macrophages laden with triglycerides and esterified sterols in the lamina propria of the mucosal layer of the gallbladder.

As a rule, cholesterol polyps exist as multiple lesions and are usually less than 10 mm. Cholesterol polyps are generally asymptomatic.

Inflammatory polyps

These lesions result from chronic inflammation. They extend into the gallbladder lumen by a narrow vascularized stalk.

Adenomyomatosis

Adenomyomatosis is characterized by extensions of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses through the muscular wall of the gallbladder. Ultrasonography reveals a thickened gallbladder wall with intramural diverticula. Although adenomyomatosis is generally considered a benign condition, serial evaluation with ultrasonography is indicated to rule out enlarging adenomatous polyps and gallbladder cancer. Some authors have reported gallbladder cancer occurring in localized adenomyomatosis and have suggested a more aggressive approach to the benign lesions.

Adenomatous polyps

Adenomatous polyps are benign epithelial neoplasms with malignant potential. Papillary adenomas grow as pedunculated, complex, branching tumors projecting into the gallbladder lumen. Tubular adenomas arise as a flat, sessile neoplasm. Consequently, it can be difficult to distinguish some adenomas from other gallbladder polyps by ultrasonography. Like many gastrointestinal tumors, an adenoma-carcinoma sequence is generally thought to occur in these lesions.

Other lesions

Other rare, benign lesions found in the gallbladder include fibromas, leiomyomas, lipomas, hemangiomata, granular cell tumors, and heterotropic tissue, including gastric, pancreatic, and intestinal epithelium.

Malignant lesions

The incidence of gallbladder cancer is 1.2 cases 100,000 persons in the United States; the frequency is much higher in Mexican Americans and Native Americans, although the greatest incidence is found in the indigenous peoples of the Andes Mountains, in northeastern Europeans, and in Israelis. The female-to-male ratio for gallbladder cancer is about 3:1; incidence of the disease peaks in the seventh decade of life.

[1]

The most common risk factor for gallbladder cancer is gallstones, which are present in 75%-90% of gallbladder cancer cases. The size of the gallstones plays a role in the risk of developing of gallbladder cancer. Gallbladders containing gallstones that are greater than 3 cm in diameter have a 10-fold greater risk for developing malignancy than do those containing gallstones that are 1 cm in diameter. Causality is difficult to establish, but other chronic inflammatory conditions, such as cholecystoenteric fistula, primary sclerosing cholangitis, pancreaticobiliary maljunction, and chronic infection with

Salmonella typhi, have also been associated with an increased risk of gallbladder cancer.

Modern series report about a 10% incidence of gallbladder cancer in porcelain gallbladders (in which the gallbladder wall is calcified), a much lower rate than that reported in older series. Stippled calcification of the mucosa is thought to carry a higher risk of gallbladder cancer than does generalized calcification of the gallbladder wall.

[2, 3] Based on these associations, chronic inflammation is postulated to be involved in the pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer.

Gallbladder cancer is often discovered incidentally during a workup for gallstone disease, and about 50% of gallbladder cancer cases are diagnosed incidentally in cholecystectomy specimens. Unfortunately, about 35% of patients have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.

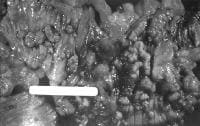

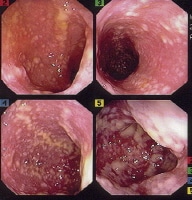

Histologically, adenocarcinoma is found in 90% of gallbladder cancer cases, and squamous cell carcinoma is found in 2% of cases. Rare types of gallbladder cancer include sarcoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, oat cell carcinoma, carcinoid, lymphoma, melanoma, and metastatic tumors. A number of histologic subtypes of adenocarcinoma have been described, but papillary adenocarcinoma represents about 5% of gallbladder cancers; it tends to be well-differentiated and carries a more favorable prognosis. (See images below.)

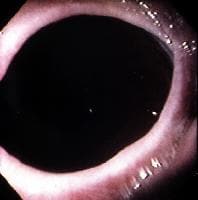

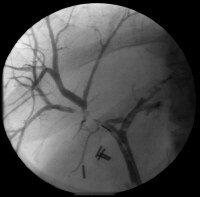

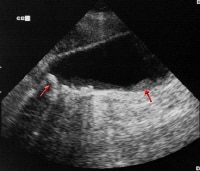

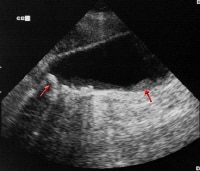

Sagittal ultrasonogram in a 71-year-old woman. This image demonstrates heterogeneous thickening of the gallbladder wall (arrows). The diagnosis was primary papillary adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder.

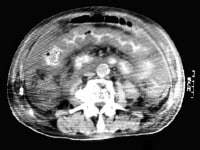

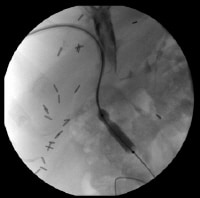

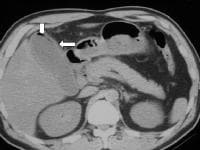

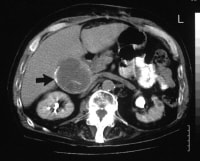

Sagittal ultrasonogram in a 71-year-old woman. This image demonstrates heterogeneous thickening of the gallbladder wall (arrows). The diagnosis was primary papillary adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder.  A transaxial enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed.

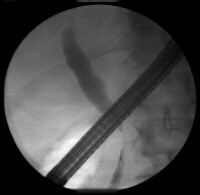

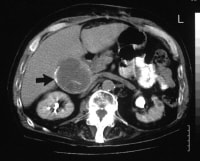

A transaxial enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of a 60-year-old man with right upper quadrant pain shows a partially calcified gallbladder (arrow). At laparotomy and histology, an infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder was confirmed.  Distal common bile duct tumor excised by radical pancreaticoduodenectomy. The tumor measured 1.2 cm in diameter.

Distal common bile duct tumor excised by radical pancreaticoduodenectomy. The tumor measured 1.2 cm in diameter.  Distal common bile duct tumor excised by radical pancreaticoduodenectomy. The tumor measured 1.2 cm in diameter.

Distal common bile duct tumor excised by radical pancreaticoduodenectomy. The tumor measured 1.2 cm in diameter.